4 states to be selected for effort to improve education, employment post-incarceration

Stateline

September 25, 2024

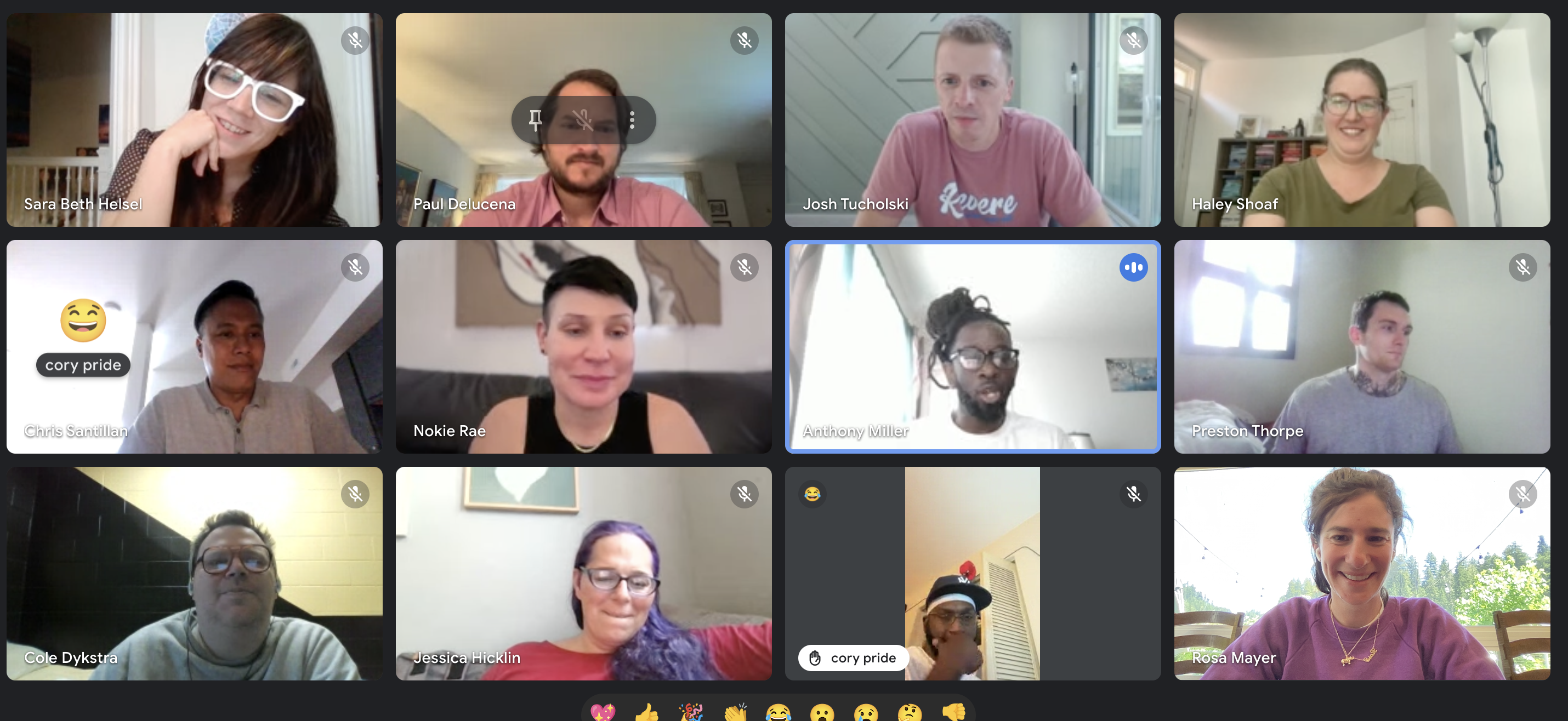

Unlocked Labs offers tech education in corrections facilities and creates pathways to quality jobs for people who are incarcerated. Three program participants say these opportunities have helped them succeed.

As a vital engine of economic activity and innovation, the tech sector offers a wide range of employment opportunities that lead to quality jobs and economic advancement.

CompTIA estimates that 5.6 million people work in IT jobs in this country, and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that there will be an average of more than 350,000 tech job openings nationwide each year through 2033. According to the BLS, the median annual wage for tech jobs was $104,420 in May 2023, much higher than the median annual wage of $48,060 for all U.S. occupations.

But people who are or have been incarcerated are often shut out of those opportunities. Security-minded corrections agencies place strict limits on access to technology in prisons and other facilities, which makes it difficult for people who are incarcerated to develop basic digital literacy, let alone take part in education and training programs in which they can build the tech skills that are currently in demand in today’s rapidly evolving economy.

At Jobs for the Future (JFF), we believe that overcoming those barriers and offering quality tech learning experiences to people in corrections facilities can play an important role in normalizing opportunity and expanding access to quality jobs for individuals with records of arrest, conviction, or incarceration.

One organization that has succeeded in doing that is Unlocked Labs, whose offerings include an offline IT training course that can be administered securely in corrections facilities, as well as a diverse set of other work based learning pathways that pay fair wages and equip learners with the skills to thrive in IT careers and contribute to a more equitable and diverse tech workforce.

Unlocked Labs is a member of the Postsecondary Education in Prison CTE Accelerator Network, a community of practice organized by JFF’s Center for Justice & Economic Advancement that supports institutions that offer credit-bearing career and technical education courses for people who are incarcerated.

Tech education programs for people who are incarcerated can deliver a range of benefits—from building on-ramps to quality jobs for people with records to expanding talent pipelines for tech employers.

To highlight the beneficial impacts these programs can have, we invited three members of the Unlocked Labs team to share their stories of how tech training and employment experiences with Unlocked Labs catalyzed their professional journeys from incarceration to well-paid quality jobs. Their insights and reflections also include advice and encouragement for other learners who are thinking about pursuing IT educations, as well as suggestions for corrections leaders and training providers about how to improve and expand such programs.

Cole Dykstra

Cole DykstraMy name is Cole Dykstra, and I am a member of the development team at Unlocked Labs. The initiatives we implemented in Maine over the past 14 years have been remarkable, and I am proud to have contributed to that progress.

My passion for computers began when I was just 8 years old, sparked by the arrival of the first Apple II’s in my elementary school in the 1980s. This early exposure ignited a lifelong interest in technology and its potential to solve problems and create opportunities.

Maintaining my skills during incarceration presented significant challenges. There are still states where books on computer programming are classified as contraband in corrections facilities, and many prison administrators view computers and other technology systems as potential security threats.

Because of this, access to computers and information in the Maine DOC was extremely limited when I began my journey.

I was fortunate to work as a clerk at Maine State Prison Industries and was able to work with other residents to develop practical solutions that addressed needs for technology access and concerns about safety in ways that gained the administration’s approval. Residents of Maine prisons can now access laptops and Wi-Fi for education and remote work. Change like this only comes from the progressive leadership of leaders like Commissioner Randy Liberty, his staff, and the administration and staff at each and every prison. For this leadership, I have deep gratitude and appreciation.

My advice to individuals who are incarcerated and interested in IT is to seize every opportunity to learn about and work with computers, enhance your mathematical skills, and practice coding regularly to build confidence and creativity.

Being able to engage in meaningful work not only helped me grow personally but also fostered a sense of community and purpose.

Cole Dykstra, Software Developer, Unlocked Labs

Corrections leaders can create more of these critically needed outlets by removing bans on computer programming textbooks, providing residents with computers and secure IT environments for practicing software development, and allowing incarcerated people to channel their time and energy into pathways to better futures.

Four years ago, when I drafted a post-release goals document, one of my top priorities was to find a “survival” job to cover my basic needs. Today, I am already able to set my sights much higher, as I am not only employed while still incarcerated, but I have a quality job with Unlocked Labs and an opportunity to expand the impact of this incredible organization to others across the nation.

Cory Pride

Cory PrideMy name is Cory Pride, and I am a 41-year-old software developer at Unlocked Labs. I’ve been obsessed with technology since I was a child. I dreamed of being a computer programmer long before I fully understood what that entailed. As I grew older and delved deeper into the world of technology, I narrowed my focus to web app development.

However, my journey into the IT and technology sector has been fraught with challenges, especially during my time of incarceration. Due to security protocols, the Missouri Department of Corrections restricted access to technology.

As society’s use of technology evolved, it became evident that allowing individuals who are incarcerated access to technology could be beneficial. Gradually, residents in the prisons were provided tablets and access to computers in the law library for small tasks like ordering canteen items. This shift in allowing more technology into facilities in turn opened the door for me to access books and in-person college courses.

A pivotal moment in my 19 years of incarceration came when I met Unlocked Labs Co-Executive Director Haley Shoaf and heard about Unlocked Labs partner LaunchCode and coding boot camps that were offered through the Washington University Prison Education Program. Meeting Shoaf and Unlocked Labs COO Rosa Mayer and former instructor Ben Clark and having the opportunity to demonstrate and grow my skills through a hands-on coding education was tremendously impactful on who I am and how I present myself today.

My advice to individuals who are currently incarcerated and interested in pursuing a career in the tech sector is straightforward: Immerse yourself in learning. Find others with similar interests, talk about it, and learn together. And, when you have the opportunity to put your knowledge into practice, give it your all.

This exposure to the day-to-day functions of a tech job was instrumental in building my confidence and making me feel capable of working on any project for any company.

Cory Pride, Software Developer, Unlocked Labs

For those with the power to create opportunities for education and training for residents—I urge you to provide the entire incarcerated community with access to tools like Canvas and Pluralsight, or access to new programs like UnlockED that are designed to help to track and share data on residents’ progress and achievements with staff and parole boards.

In my own case, the opportunity to continue working with Unlocked Labs after my release has significantly impacted my career trajectory. I entered the company with valuable skills but through Unlocked Labs I was able to work side-by-side with senior developers, project leads, and UX designer teams. This exposure to the day-to-day functions of a tech job was instrumental in building my confidence and making me feel capable of working on any project for any company.

I am committed to using my skills to make a positive impact on others and to advocate for the continued expansion of educational and technological access so that other people who are incarcerated have a similar opportunity to access the transformative power of education and technology.

My name is Preston Thorpe, and I am a resident at Mountain View Correctional Facility in Charleston, Maine. I am also a tech team lead for Unlocked Labs. I have been incarcerated since 2013, except for one year in 2016. I came to the Maine system in 2019 and immediately knew that it was an environment that would allow me to make a major change in my life.

Due to forward-thinking leaders and dedication to rehabilitation over punishment within the Maine Department of Corrections, I have been able to focus my thoughts inward on myself and my future without many of the distractions that plagued my younger years in prison. After enrolling in college and receiving access to technology for my education, I recognized an opportunity to improve my life by devoting myself to learning a skill that could change my life upon my release. As a “computer geek” in high school, I chose computer programming as a prospective career and dedicated the remainder of my sentence to becoming as valuable a software developer as I could be.

At first, learning these particular skills with such limited resources was challenging, as security concerns are always an obstacle when residents are given access to technology. Luckily, I had a background in programming and technology from high school, which helped me overcome these challenges by using my existing technical knowledge to help the Education Department establish the technical infrastructure for resident education in Maine facilities. Over time, I was able to build trust with the administration, which eventually granted me permission to contribute to open-source software projects on GitHub (a worldwide platform for collaborative software development). This was a major turning point for me. I started communicating with developers from all around the world and gained real-world experience and visibility in the tech community. I spent 10 to 14 hours a day learning everything I could, building side projects, contributing to open-source software, and developing in-house solutions for the Maine Department of Corrections.

I have been able to build an impressive resume, gain substantial real-world experience, prepare financially for my release, and develop a network of contacts in the tech industry.

Preston Thorpe, Tech Team Lead, Unlocked Labs

Later, I was granted permission to look and apply for remote work, as one of just a handful of residents chosen for this experimental program. My expectations were low because I had no professional experience and was still incarcerated. After a few months of searching, I connected with Unlocked Labs and was brought on as a software developer on a temporary contract. I worked hard to prove myself, including spending more than 90 hours a week on programming and developing new, relevant skills. Soon after the initial contract was up, I was offered a permanent, full-time position. I have since been promoted to senior developer and I now lead their software development team.

The Maine DOC staff have been extremely supportive in my journey, allowing me to prove myself and granting me the appropriate access needed to advance my skills and career. Their support has been crucial to my development and success. Although I am still incarcerated until May 2025, I have been able to build an impressive resume, gain substantial real-world experience, prepare financially for my release, and develop a network of contacts in the tech industry—all things I would never have achieved without the Maine DOC’s willingness to take a chance on us and provide us with the resources to help ourselves.

I spend much of my free time mentoring other residents who are interested in programming and encouraging them to spend their time in ways that will benefit them upon their release. Time is the most valuable asset residents have, and we can take advantage of it in ways that most people on the outside cannot because we have fewer outside responsibilities and distractions.

The stigma of a record is real, and for most employers, it will almost always be the easier decision to hire an applicant with equivalent skills without a record. So, until opportunities for people with records to work in quality jobs are considered normal, developers with records must work that much harder and be willing to spend more time learning and becoming a more competitive job candidate and valuable employee. Fair chance employers also reap the benefits of having employees who are thankful for the opportunity and willing to show their gratitude for being given a fair chance with continued hard work and loyalty.

But no one deserves to forever be defined by their worst mistake, and a record is no indication of someone’s knowledge, skills, or ability to perform their job. So, how do we get to a place where we have normalized opportunities and prepared people with records to work and succeed in quality jobs in the tech sector? We humanize those who are still currently incarcerated and leverage increased access to education and technology to extend pathways to those quality jobs to begin in correctional facilities.

I’ve also spent years in prisons in other states, and during that time I never made any changes to my attitude or behavior because I had limited opportunities to learn and to better myself. It’s difficult to change when you are surrounded by the same negativity that brought you to prison and are never shown a different path. If we want the carceral system to truly be about corrections and rehabilitation, we must offer those who reside in facilities a choice—a choice to change their trajectory, to pursue a path aligned to their interests that leads to a quality job and a chance for a better life.

Stateline

How to Catalyze EdTech Deployments for People Who Are Incarcerated The following recommendations are steps that six sets of stakeholders—corrections leaders, postsecondary leaders, employers, solutions providers and technologists, investors, and policymakers—can take to catalyze the…

Vehicles for Change City: Halethorpe, Maryland Year Founded: 1999 (Vehicles for Change); 2016 (Vehicles for Change-VR) Website: https://www.vehiclesforchange.org/ Segment: Learning Content Provider Measures of Success Virtual reality training program reduces training time by 60% VR…