A Successful Post-Prison Reentry, With Support at Every Step

April 28, 2021

At a Glance

One year out of prison, Chicago’s Jackie Helm is happily employed, thanks to a transition program for people with criminal records and employers willing to assess on skills, not stereotypes. Our experts offer 5 key strategies to ensure people with records get a fair chance.

This blog post is the first in a series, Making the Case for Fair Chance Hiring.

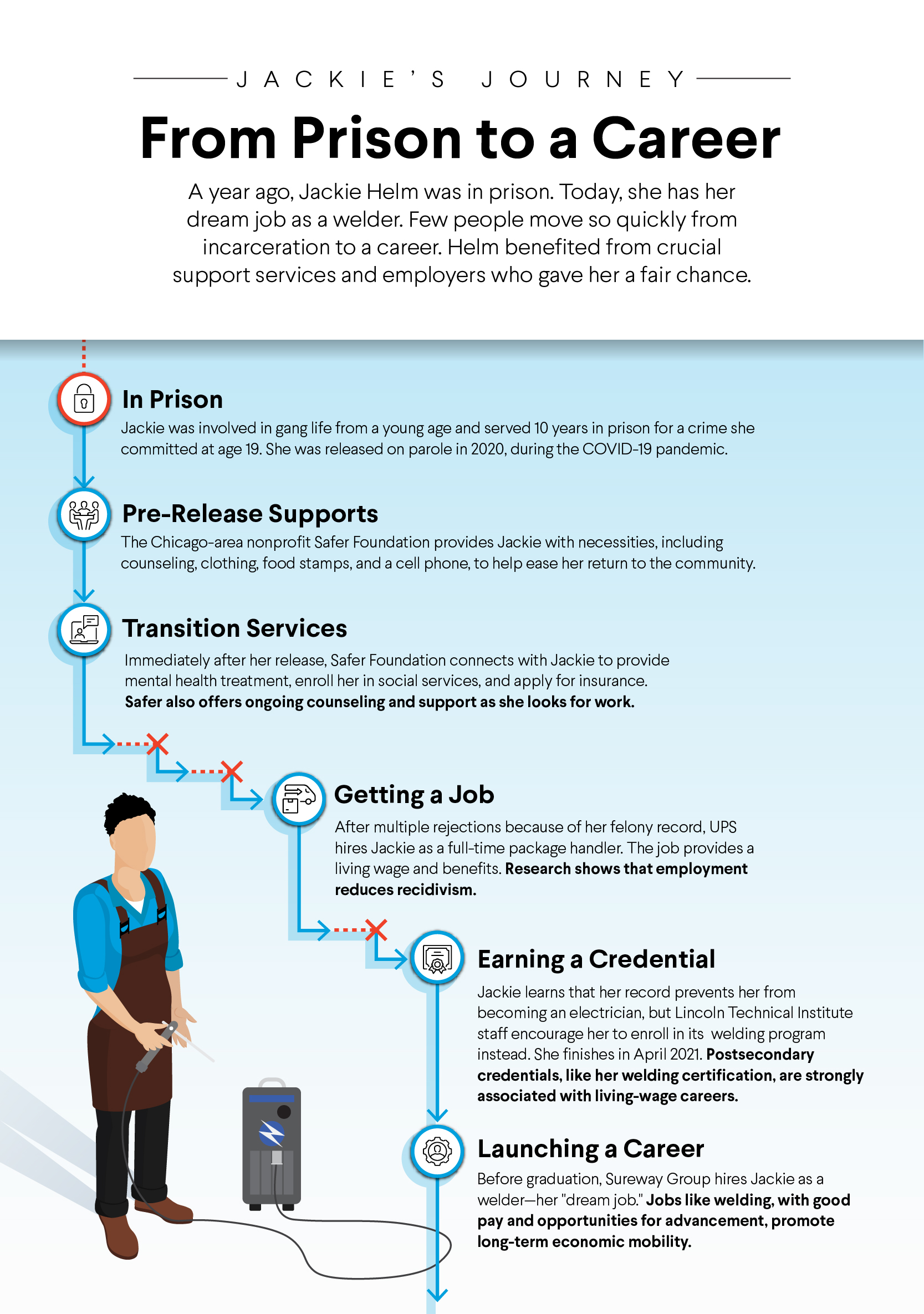

Jackie Helm came up hard, and all alone in Chicago. She was involved in gang life from a young age and at 19 committed a crime that sent her to prison for a decade. She spent her entire 20s behind bars and was released last year, in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When Jackie Helm left prison, she’d missed an entire decade of education, employment, and personal growth. She found few resources in incarceration. “In the inside, they don’t really have anything, especially for women,” she says. And because she was up for parole during the coronavirus pandemic, social supports and work opportunities to smooth her return to the community were scarcer than ever.

A year later, Helm is employed, in school, and learning welding—an in-demand trade that’s not common among women, but has become her dream job. After earning her American Welding Society certification in April, she’ll work full time at a Chicago-area metal fabricator, the Sureway Group.

Helm’s path may sound like a simple success story. But she’ll be the first to tell you she didn’t reach this point easily, she didn’t do it alone, and she believes other people exiting prison deserve the resources and opportunities to heal and thrive. People who have served time in prison need holistic support—ideally, starting well before their release dates. And more employers need to examine their policies to ensure that people coming out of the prison system get a fair chance.

Research shows stable employment is associated with reduced recidivism. For Helm, finding a good job made the difference between getting out of prison and truly being free.

People say, ‘Why don’t they pull themselves up by their bootstraps?’ But you know, we’ve cut off the bootstraps. They don’t even have boots.

Victor Dickson, CEO, Safer Foundation

The United States is a carceral state, with less than five percent of the world’s population and more than one quarter of its prisoners. Right now, there are 77 million people in the United States with criminal records. Most are men, but the rates of incarceration for women are rising. More than 600,000 people are released from state and federal prisons every year. The nation’s stain of mass incarceration goes hand in hand with the legacy of racism: Black, Latinx, and Native American people make up the majority of the incarcerated population, and they are similarly disproportionately represented among the reentry population.

Most people leave prison with $20 to $50, the phone number of a parole officer, and a wave (maybe) on their way through the gates. Once a person gets out, they find obstacle after obstacle: shaky or no social support, technologies that have passed them by, the need for housing and health care, and the dual stigmas of racism and incarceration bias. Even things that are routine but necessary, like obtaining a form of state-sanctioned identification, present a huge hurdle for those recently released. Women face a unique disadvantage; according to the Women’s Prison Association, policies and interventions are primarily designed for men.

A Chicago-based nonprofit called Safer Foundation, which provides essential transition services to people with criminal records, helped eliminate those barriers for Helm. Safer is a 50-year-old social justice organization dedicated to reducing recidivism by providing a full range of services, training, and a clear vision: “achieving equal employment opportunities for people with criminal records, thereby transforming communities and generations.”

In the face of the national COVID crisis, the governor’s office asked Safer to broaden its programs to aid the hundreds of people in the Chicago area who were receiving sudden, unexpected release to reduce virus transmission. Helm was up for parole at this time and Safer was able to serve her, too.

I want to build the stadium I drive past and say, ‘I made that.’

Jackie Helm, the Sureway Group

“We spearheaded an effort with several other agencies to do the most basic things like giving people care packages that included clothing, food, and even cell phones,” says Safer CEO Victor Dickson. Safer also helped Helm get health care, food stamps, and identification, all crucial steps on her path to employment.

The social supports that organizations like Safer provide are key to successful reentry. Unfortunately, they’re only part of the solution. Rules and restrictions about hiring people with convictions vary from state to state, and long-held stereotypes and biases make it nearly impossible to get and keep a job. When you get out of prison, no matter how much you might have changed, you’re unlikely to get a chance to prove it.

“When I came home, I was very stereotyped,” Helm says. “One thing was because I was in prison for a while. The other thing was that I didn’t have any [work] in my background. I have a lot of talents but no experience at all.”

Helm benefitted from employers who were willing to look beyond her record to see a talented woman and a strong worker. Her first post-incarceration job, as a package handler at UPS, came through a supervisor who also had a criminal record and hired her because he thought she’d be a good fit. Helm proved him right, working through a challenging holiday season (no small feat!) and earning a chance at a promotion. But she turned it down. Helm wanted a meaningful career, not just a job. “It wasn’t what I wanted to do,” she says. “I said, ‘I’ve lived so long with not being happy, I want to be happy.’”

Lincoln Technical Institute helped Helm break through the final barriers to a stable, living-wage career. When she tried to enroll in the school’s electrical training program, she learned that Illinois Electrician Licensing Act prevents people with felony convictions from becoming licensed. But the staff didn’t let Helm walk away; instead, they guided her to the welding program, which had fewer licensing restrictions. Welding, with average pay of $23 per hour in the Chicago area, has proven to be a great fit: “I’m happy, I’m satisfied now,” Helm says. “I want to do more welding, the more advanced stuff. I want to build the stadium I drive past and say, ‘I made that.’”

I’m excited about my journey moving forward. I hope it helps someone else.

Jackie Helm, the Sureway Group

Helm is on her way to becoming what Safer strives for in its mission statement: an employed, law-abiding member of the community. In a field where just 7 percent of local welders are women, she is also a role model for others who want to pursue welding.

It’s easy to say that Jackie Helm is exceptional—her drive and positivity have helped her achieve her dreams. But people with criminal records shouldn’t have to be exceptional to get the supports and opportunities that will allow them to find stable jobs and housing. Our current system, unfortunately, demands nothing less.

“People say, ‘Why don’t they pull themselves up by their bootstraps?’ ” says Dickson, Safer’s CEO. “But you know, we’ve cut off the bootstraps. They don’t even have boots.”

Nobody can make it through this world barefoot. Reentry success begins in corrections, with organizations like Safer Foundation providing support through every phase of an individual’s return to the community. It’s also up to policymakers to change restrictive laws, and employers to look beyond criminal records and provide people with a fair chance at being hired. That’s what Helm says employers can do for people like her: “Give us a chance.”

It’s time that employers and social service organizations begin to meet people who have served prison sentences with what they need to start taking steps forward, away from the prison gates.

Here are five ways to ensure people with records get a fair chance:

- Start supports before reentry. Helm started working with Safer Foundation staff while she was still in prison, and they have continued to support her every step of the way after her release on parole. Building a continuum of education and training that begins during incarceration and continues when people return home increases the likelihood of success.

- Link supports, education, and training. Helm was incarcerated as a young woman with limited employment skills and many personal difficulties, and spent ten years in an environment that inflicted new trauma and mental health challenges. Safer ensured she received support services to help her heal from the trauma she experienced both before and during incarceration. That prepared her to work effectively with Lincoln Tech, which ensured that when one training was closed to her there was another available.

- Eliminate corporate and policy barriers to employment. Many employers consider a criminal record to be an automatic disqualifier for job candidates. State and regulatory policies that limit or prohibit people from getting (or keeping) a job also create thousands of collateral consequences. Helm’s employers—UPS and Sureway—had policies that focused on the skills she could demonstrate rather than the mistakes she had made, and they were able to hire an exceptional employee.

- Change the narrative about people with records. Helm has proven to be an excellent student and an excellent worker, but this runs counter to existing narratives about people with records—especially people of color—as risky employees and perpetual threats to community safety. We need to flip that narrative. People with records should be assessed, whether for work, housing, or rights of basic citizenship, based on the assumption that they can and will make a positive contribution to their communities.

- Remember the women. While men are the overwhelming majority of the people incarcerated, the incarceration rates for women are rising. But few programs recognize women’s unique needs in prison or in reentry. For example, recognizing the prevalence of trauma among women who are incarcerated requires more tailored forms of mental health treatment. As Helm noted, women are also too often left behind when it comes to training, opportunities, and services.

This work was generously funded by a grant from the the Justice and Mobility Fund at Blue Meridian Partners. The Justice and Mobility Fund is a collaboration launched by The Ford Foundation and Blue Meridian Partners with support from the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies.

Related Content

Freedom to Achieve: Pathways and Practices for Economic Advancement After Incarceration

More than half a million people are released from U.S. prisons each year, and the majority are unable to find work due to underlying biases and systemic racism. This report argues that we must match…